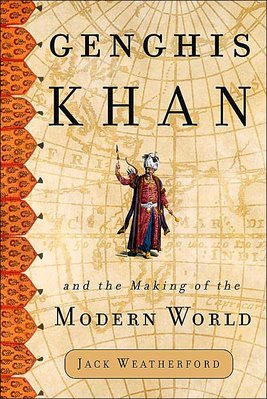

In "Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World", Jack Weatherford does a great service to the resuscitation of the 13th Century Mongol conqueror’s reputation and legacy. Genghis Khan is often depicted in popular and academic writings as a bloodthirsty savage who relished the acts of torture and genocide. Weatherford’s Genghis Khan is a misunderstood genius who created an empire that was in many ways centuries ahead of the ones created by Chinese, Muslim and European civilizations that the Mongols subjugated.

Genghis Khan created a new nation after decades of war within the areas we call Mongolia and Inner Mongolia (a part of China). The nomads of the steppe had always clung to their tribal identities and when one of them grew too strong, the sedentary civilizations of China and Central Asia conspired to pit one tribe against another. Genghis Khan broke this pattern and instead forced the sedentary civilizations to conform to his interests and will. He did so by placing merit above birth in choosing his generals. Women enjoyed far greater rights and freedom under Mongol laws than under any of the civilizations they conquered.

Perhaps what distinguishes Genghis Khan over other conquerors was the remarkable durability of his empire. Though the greatest conqueror of all time in terms of landmass, Genghis Khan’s heirs continued the Mongol conquests and subjugated Russia (1240s), Iran and Iraq (1250s) and China (1260s-1270s) and instituted a century-long Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace, that drove civilizational contact among Europe, India, China and the Middle East.

In fact, Weatherford makes a strong case that it was this very commercial and cultural exchange that sustained Mongol power long after they had grown soft and their military edge had waned. He also makes a strong case that the Black Death that arrived in Europe in 1347 from Mongol Russia had in the decade before done what no army of man had been able to do, disburse and ultimately end the Mongol Empire. Once the devastation and depopulation of the plague had cut the connections between faraway nations, native subjects throw off their Mongol overlords and the Mongol Empire evaporated. By the 1380s, direct Mongol power was limited to the steppe.

Weatherford does a very good job of making the (very) foreign Mongol and Asian geography and languages accessible to American readers. He also does not get bogged down with every significant flair up in Mongol politics (Golden Horde vs. Ilkhan wars, etc.) while providing enough detail to let readers know and understand the major fault lines within imperial Mongol politics.

Since 2006 is the 800th anniversary of the election of Temujin as "Genghis Khan" and the creation of the Mongol state in 1206, it is fitting that we have such a valuable and easy to read book as Weatherford’s to instruct us. I highly recommend this book to novices and history buffs alike.

No comments:

Post a Comment